Honduras: The neighbors of the South have damaged kidneys

The Central American Pacific coast is plagued by communities where people live marked by chronic kidney disease. To this diagnosis numerous studies have added nontraditional. It means that it is not preceded by other basic diseases and also appears at an earlier age. Those affected agree to work in agricultural activities and reside as neighbors of massive crops. This is the first chapter of a series that will address the phenomenon. This is about Honduras.

Lea este artículo en Español: Los vecinos del Sur de Honduras tienen dañados los riñones

Ángel Ortega raises his arm and points with his finger. Eight hundred meters away from his house, where he’s pointing, is a field that right now appears empty, but that very soon will be filled with melons as far as the eye can see. Ángel lowers his arm quickly, he can’t hold it in that position any longer. His veins are swollen, showing knots, and his skin looks withered. Angel was diagnosed with chronic kidney disease five years ago, in 2015, and has been receiving kidney dialysis since then. He is in great pain most of his days and nights.

The 2018/2019 melon harvest was historical for Honduras. The international prices soared up 45% from previous years. The Honduras Central Bank estimated the value of exports to have raked in some 110 million USD The big melon producer is in the zone of the Choluteca and Valle, known as The South, bordering El Salvador and near the Pacific Ocean. Ángel points to the place where the melon plantation is, to the right side of his house. He says that if you walk one kilometer through the community, you’ll find sugar cane fields.

In 1977, Ángel arrived at Monjarás. This is one of the 23 villages of Marcovia, in the area of Choluteca. Eleven years later, in 1988, he managed to buy a piece of land to build his house. He arrived when he was 20 years old, seduced by the job prospects and the chance to have a place to stay. Every day he, and thousands of young farm workers, got up at 3 a.m. and went to the field. By 8 o’clock he was done with one tarea and began another. He did so until 4 in the afternoon, when he stopped working in the fields of others to work on his own piece of land. On his own land he planted corn and beans. This impossible schedule is normal life for almost all of the men working as agricultural labourers in Monjarás.

Now, Monjarás has 7,500 houses, 16 schools, two banking agencies, about 20 clothing stores and some restaurants. And Ángel doesn’t work anymore. He spends his days on a hammock that hangs on the outside corridor of his brick house. The house has an exterior latrine, like many houses in this area. Four years ago, when Ángel was diagnosed with chronic kidney disease, his diagnosis was common in this area; as common as the brick houses and the outside latrines.

Chronic kidney disease has two categories. The traditional one presents itself along with other diseases like diabetes and arterial hypertension. The other, the kind that Ángel suffers from, is more complicated to name. One of its characteristics is that it appears in patients who have no previous history of disease, and at an earlier age in comparison with traditional kidney disease. This new kind of kidney disease presents, in fact, among people belonging to certain social conditions.

Prevalence studies of this disease that were carried out in the region indicate that patients have two characteristics: that they work in agriculture and that they live in areas where there are massive crops. One of the first studies was made in El Salvador in 2009 and was called NefroLempa. It was directed by Salvadoran nephrologist, Carlos Orantes, who is an advisor to the Group of Experts in Sri Lanka for the approach of Cronic Kidney Disease (CKD) that affects agricultural communities; he is the author of scientific publications in international journals and has recently published chapters on the subject in the book Internal Medicine and Cynical Nephrology at the University of Oxford. Orantes has been a visiting professor in the Nephrology division of the Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Harbor-UCLA Medical Center and Cedars Sinai-Medical Center.

“Some people choose to call this a disease. But it’s an epidemic”, says Orantes without any hesitation.

“When your focus is from the point of view of on the individual, the phenomenon of CKD is limited to the signs, symptoms and how it presents in the individual sick person. This is traditionally how the medical profession approach CKD and that is how they then treat the individual” Orantes says.

“But when this disease presents itself not in one or two or three people, but in hundreds and hundreds more, in a specific geographical, social, environmental area, and all the people affected share the same specific unhealthy working conditions born from the current agricultural productive model, then it’s no longer an individual problem but a problem on an epidemic level affecting whole societies.”

Orantes is speaking from one of the meeting rooms in the Health Ministry, in downtown San Salvador, El Salvador – a five hour long busdrive from Monjarás. He gained his knowledge on the matter in the communities he visited and worked in. He has written and published his observations about them in various medical magazines like MEDICC Review.

From Mexico to Panama, all through the Central American Pacific corridor, nontraditional chronic kidney disease presents in high numbers, which is the reason why specialists have called it “Mesoamerican nephropathy”.

“This is a population phenomenon; we are not talking about a disease anymore. We are talking about an epidemic. And because it affects more than two countries, this is already a pandemic,” explains an alarmed Orantes, one of the leading authoritative voices in Latin America about this matter.

In Monjarás, Ángel and his neighbors don’t actually say it, but they have experienced this pandemic in the flesh for many years, a pandemic that has rooted itself in the agricultural communities of the Pacific with no end in sight. Honduras only has data by area and not by community. Between January 2018 and June 2019, 202 Choluteca patients were hospitalised for chronic kidney disease.

***

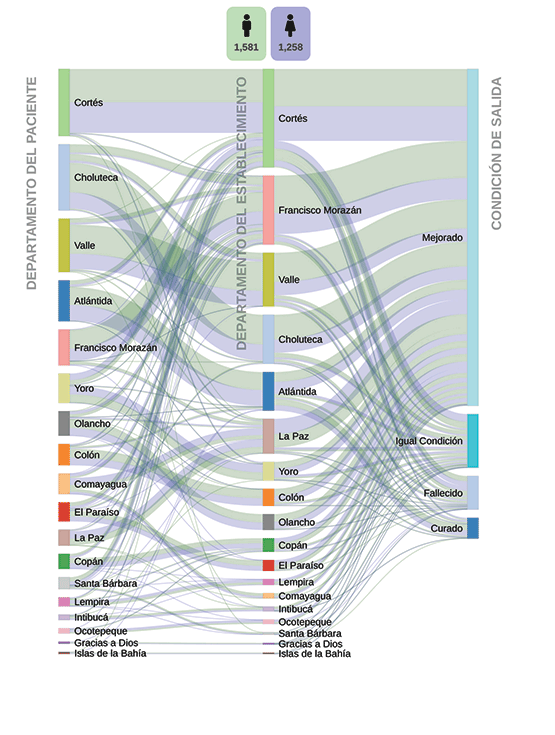

Honduras is divided into 18 areas, with a total population of 9.2 million people. Choluteca and Valle are the two areas that have the highest rates of chronic kidney disease. Between 2016 and 2017, 2,839 people were diagnosed with it in the public hospitals of Honduras. 30% of the diagnosed people said they lived in those areas.

Choluteca and Valle are also the two most productive areas in the country. In 2016, the South Honduran region alone delivered 16,000 20 foot containers full of melons for the international export market. For 2019/2020, the yield will only go up: melon will increase by 13%; okra by 19% and watermelon by 50%, economists predicts. From all this, the priority for the Central Bank in Honduras is the income produced and the jobs created.

“This is the region that produces most wealth for the country, but look around you! You wouldn’t say so!” says Marcos, standing at a dirt road running through Monjarás. Marcos is a community leader who prefers to remain anonymous because in the area of Choluteca more than a hundred human rights defenders have received death threats.

Marcos is wrong though. You can tell there is development in his community, but maybe not in the way he would want it. Studies show that farmers contracting chronic kidney disease is directly related to the presence of massive crops. One study that followed 34 patients in four countries over 12 months concluded that there was ‘a specific lesion that occurred in patients with chronic kidney disease from the farming communities. This work was published in 2019. “We suspect the pesticides used for agricultural purposes are the cause responsible for this nephropathy,” explains Marc de Broe, one of the specialists who participated in the study and signed the final report.

In his house, Ángel remembers what his work used to entail: “I sprayed the venom with the fumigating pack on my back starting at 4 a.m. At 8 a.m. I stopped, when the women brought me food. Once, a tank full of Metil 800 fell over me when a tractor had an accident. I was soaked and went blind from it. The tractor driver took me to the river and left me in the water for about half an hour. No matter how hard the women washed the clothes, they turned yellow”.

Ángel speaks openly in front of his family. Although he’s the only one officially employed by numerous farming companies around Monjarás, all the members of the family that live in this house have been exposed to agrochemicals like glyphosate and paraquat. But these family members are not recognised by the sanitary system or the massive crop companies. “People who live in the farming communities are at higher risk of contracting chronic kidney disease,” according to the investigation published by the Sanford University of South Dakota. Monjarás is the perfect storm for kidney disease: near to massive croplands, with direct or indirect contact with nefrotoxic agrochemicals and dubious water quality.

“One study that followed 34 patients in four countries over 12 months concluded that there was ‘a specific lesion that occurred in patients with chronic kidney disease from the farming communities.

***

The four most profitable products of the South — melon, watermelon, okra and shrimp — earned 304.8 million US dollars in foreign exchange for Honduras in 2018. What is produced here, travels to the markets of Germany, Colombia, El Salvador, Ecuador, Spain, France, Japan, Mexico, United Kingdom and Taiwan, among others. What’s left behind after such a production is, however, an empty landscape. Inhabited, yes, but by people who coexist with death.

Marcos, the community leader in Marcovia, Choluteca, just 14 kilometers from Monjarás, has come to visit Ángel: “Everywhere you look there’s a house with someone ill or someone who already died from it.” This is no exaggeration. Marcos and Ángel are calculating the number of deaths and sick people directly surrounding them: behind this house, a man died a few days ago; to the front, there, left, somebody else is sick. If you ask to your right, there are also sick people. If Honduras had a map with a red dot placed on every house where there’s someone with kidney damage, the community of Monjarás would look like a red blanket. But Honduras doesn’t have such a map, nor does it have studies that go deeper into the causes of this epidemic. The only certainty is the number of people diagnosed. Between June 2018 and June 2019, 3,085 people with chronic kidney disease were treated in public hospitals in all Honduras. 806 of them came from Valle and Choluteca. These two areas, from a total of 18 in the whole country, account for 26% of all recorded cases.

The rise of melon production has been meteoric. The 2017/2018 crop produced 70 million dollars in exports. Estimates for the 2018/2019 crop predicted that it would rise up to 90 million dollars, but the projections fell short, and in reality exports surpassed 110 million.

At home, Ángel is making another calculation. “Three of us got together to pay the for a taxi to go to Choluteca to receive treatment, so it wouldn’t be so expensive.” Ángel made this 31 kilometer trip with his friends, Rosa and Maura. The taxi costs 600 lempiras ($24 USD) from Monjarás to Choluteca, where the Dialysis Hospital is located. This hospital provides the service because it is subcontracted from the government to do so. “Between my friends, Rosita and Maurita, we only paid 200 lempiras ($8 USD) each,” says Ángel before adding and subtracting. “A year ago, Rosita died and so Maurita and I remained and payed 300 ($12 USD) each, to go two times a week.”

Dialysis is a treatment where a machine basically does the work a kidney would usually do. Patients must remain connected to this machine between four to six hours. Depending on the state of the patient’s kidney, two or three trips a week could be needed. “I was left by myself paying for the trip after my friends died,” says Ángel. Maura died last August because of complications due to the reduced kidney activity. Ángel is the only one remaining.

http://guilles.website/dev/honduras-ecr/datavis.html

***

Chronic kidney disease is a phenomenon concentrated in the Pacific Ocean corridor of Central America. In 2013 it became the reason for a meeting among the Health Ministries of Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua and Costa Rica, who met in El Salvador to declare the investigation of this problem as a regional priority. In a joint statement, the highest health authorities of each Central American government agreed to give medical treatment to those affected and to give high priority to study the causes and the risk factors of the disease.

“Honduras hasn’t provided input to the studies about the disease in the same way that Nicaragua, Costa Rica and El Salvador have. El Salvador is at the vanguard of information and Guatemala also has info, but not us. Not because we don’t have huge numbers of patients, but because we don’t have any resources or because we don’t want to admit how big this problem actually is,” explains Gemmer Espinoza, from his private clinic. Espinoza is a nephrologist. He is also the only one in Choluteca.

Espinoza also works in the Dialysis Hospital. Because of his experience there, he has been able to build a profile of patients with chronic kidney disease. They are, overwhelmingly, agricultural workers. But also, almost inevitably, they are people who live in the vicinity of massive croplands.

In Monjarás, the dusty streets fill with people around sunset, once the heat has dropped down a little. Youngsters exchange snacks in the corners and little kids ride bikes. If it rains, there will be puddles of water, some puddles stretching for meters. If the day is dry, clouds of dust will rise. Sometimes, pending the direction of the winds, strange smells waft over the village and houses from the direction of the crops. The most pungent smell is noticeable just before dawn when planes fumigate the plantations.

Espinoza cannot support his observations with any medically recognised study because he has not written it yet. But he points out that 80% of the cases arriving at the local hospital are in stage 4 or 5 of kidney failure, meaning that the kidneys have lost almost all their filtering capacities and the dialysis is needed to extend the life of the patient.

The Honduran State pays around $100 USD per patient to the private company that provides this service, according to sources that asked to be kept anonymous. Indirect payments for the treatment, like bus or taxi fees, like the ones payed by Ángel and his sick friends, come from their own pocket.

Living in this region increased the likelihood that Angel and his family would suffer from chronic kidney disease. And although the Honduran authorities have information that confirm it, this evidence has not been enough to provide and organise services, educational campaigns, early diagnosis or treatments. Save for the presence of patients that gather every morning in the hospital to receive dialysis, this disease is invisible rather than the medical catastrophe that it should be.

“El Salvador, Guatemala, Costa Rica and Honduras agree that people who are sick, are related in most cases, with massive agricultural farms and crops. We must remember that there has always been farming in our countries, planting corn-beans, corn-beans, for survival. What makes this different, is the massive scale of farming and production and the use of chemicals,” says Espinoza. “It’s hard to sustain this without arguments, because in Honduras we don’t have studies, but all the research from other countries point towards the use of pesticides.” At least 29 brands of Glyphosate and 19 brands of Paraquat are marketed in Honduras, and indication of the scale of nephrotoxic substances in crops. These are two of the agrochemicals that scientific studies relate to kidney damage.

In front of Ángel’s house, some men have passed by, riding their bicycles. It’s the end of the afternoon and they have done their work. Four years ago, Ángel was also riding those streets in his bicycle when suddenly he felt so dizzy, he had to stop.

“I already had a high fever, and I started feeling cramps on my legs. I send the güirro (boy) to buy me some pain killers and a juice,” he tells. But Ángel didn’t get better with the pills and the juice. Eventually he had to go to the hospital. In fact, he went to a few hospitals. His diagnosis came late, even with knowledge of where he lived and the nature of his work, because the health system isn’t focused on providing a prompt treatment for these cases. It took at least four months to receive a diagnosis of chronic kidney disease and to start the only treatment: dialysis.

This lack of convincing arguments as to the nontraditional causes of the disease has also delayed the development of programmes focused on the special needs of the population, such as early diagnosis. Manuel Sierra, member of the Medical Sciences Faculty of the Autonomous University of Honduras, directed a study in 2019 about the prevalence of kidney damage in patients from the six biggest hospitals in the country. “We made a screening question to people older than 18 years who were receiving treatments in Internal Medicine: ‘Have you been diagnosed with kidney disease’? If the answer was positive, they couldn’t participate any more.”

“People who live in the farming communities are at higher risk of contracting chronic kidney disease,” according to the investigation published by the Sanford University of South Dakota. Monjarás is the perfect storm for kidney disease: near to massive croplands, with direct or indirect contact with nefrotoxic agrochemicals and dubious water quality.

Researchers found that 774 patients said they didn’t have any kidney damage. But according to the tests results, only 20% of these answers were true. “82% of people who reported that they were healthy, did have some level of damage: 8% in stage 1; 28% in stage 2; 30% in stage 3; 10% in stage 4; and 6% in stage 5,” explained Sierra. That means that 8 out of 10 people who went to the hospital for other reasons already had damaged kidneys and didn’t know about it, and are not taking care of their kidneys nor receiving the proper medical treatment. They are only waiting to collapse, just like Ángel did, four years ago.

Between January 2018 and June 2019, 197 people died in public hospitals from chronic kidney disease in Honduras. The day when Ángel had to interrupt his bicycle trip, he was going to the funeral of a friend, El Chuta, a neighbor and farmer like himself. El Chuta died from the same disease that has Ángel lying on the hammock. Ángel has been watching his friends die for a while now.

The study into the prevalence of non-diagnosed kidney disease is being repeated, but now exclusively in the zone of Choluteca, according to Doctor Sierra. While this happens, in Ángel’s community, the one with the houses neighboring massive croplands and people who drink water from wells, kidney disease is like the Grim Reaper invisibly moving across farmlands taking with it many people. It also brings fear. “Until now they (his family) don’t suffer from this, but this disease is a bitch. I see my wife and my son both with the same cramps already. Here you never know, that’s the saddest part of all.”

* Glenda Girón is a Bertha Foundation Fellow of the 2019-2020 generation