Living and dying between crops: Chronic Kidney Disease in Chichigalpa

Chichigalpa is a municipality of Chinandega, Nicaragua. Here it is impossible to separate the residency areas from the agricultural ones. The houses grew among the crops of –mainly- sugar cane. The dilemma is that what is good for agricultural production it does not equally beneficial for the residents. Sugar industry workers were the first to be detected with Chronic Kidney Disease.

A company, producing sugar and its derivatives, provided housing and basic services to entire colonies of people. They were tenants, thousands of tenant farmers who lived with the smoke from the burning of sugar cane fields, as well as with the spray of agrochemicals thrown by the planes. That’s how it was just over 20 years ago, when braceros, paileros, fumigators and their families lived inside San Antonio sugar mill, toward the Pacific coast of Nicaragua. There were farmer’s markets on weekends, there were days of house cleaning and medical ones. Also, people celebrated birthdays and weddings. People had a home, a job and a family. They were a community, the community that lived and kept alive the San Antonio sugar mill of The Nicaragua Sugar State in Chichigalpa, Chinandega.

Chichigalpa, this hot municipality of narrow streets, was completely changed by three events. The first one was the eruption of the Casitas volcano in October 1998, which left hundreds dead and displaced. In November of that same year, Hurricane Mitch flooded and carried what little was left standing in the mud. The third was of a population’s nature, a movement unprecedented until then: The San Antonio sugar mill removed all the tenants from the sugar mill’s lands. They were thousands. It was 1999.

“Let’s put it this way: Chichigalpa originally had 174 acres. The amount of land that the mill bought for the tenants was, at first, 104 acres. But they got to buy 174. So Chichigalpa practically doubled when they founded La Candelaria”, says Víctor Sevilla, who was mayor of this municipality for three periods. Those extra lots that the mill bought, explains the former mayor, were divided. For each one, two families were placed. “The latrines were so close together that when it rained, overflowed,” says the mayor who puts his hands together to illustrate the distances and extends them as far as he can to illustrate the overflows.

The impact was not only of demographic density. People in those new settlements started to get sick. The common diagnosis: Chronic Kidney Disease. People recently moved from the San Antonio sugar mill to La Candelaria, and other scattered in smaller settlements, began to see their kidney function deteriorate rapidly. From that beginning of the 2000s, people remember that they came from burying one when they had to take another person to the cemetery.

The former mayor does not want photos taken, nor does he get out of his car for this interview somewhere in the middle on the road, outside the city. But he says one thing for sure: “People were taken out of the mill because they were going to start dying and that’s how it was.”

“Our houses, our regions, our cities such as Chichigalpa, El Viejo, Pozoltega, Quezalhuate, and León itself, all are in the middle of the sugar cane fields. The natural environment of these populations is sugar cane,” explains the former mayor Sevilla.

***

NICARAGUA IS A COUNTRY THAT WAS SPLIT IN 2018.

Protests against government decisions about social security filled the streets. There was violence and repression. From this event, fear and political polarization are taken to the extreme. Since Daniel Ortega regained presidential power in 2007, the government has obscured his entire management. And, after the recent day of protests, government activity became more secret. In this context, government institutions are not used to providing data. It happens with the statistics of violence and with those of hospitals. The data, if there is any, is not public information.

A study dated 2003 includes, to illustrate the number of diagnoses, a map in which each point is a dead person. The points are concentrated in the departments of León, Chinandega, and Managua, on the side that this country faces the Pacific Ocean. The same strip in which the cases of Guatemala, El Salvador, Honduras, and Costa Rica are also concentrated. This study was carried out by the Nicaraguan Ministry of Health and is one of the few official documents that are available in this regard. At the time, the alert was noticed because in 1990 were only 200 deaths, and it jumps to 500 in the 2000s. “Between 2004-2006 there were more and more cases, but we do not know how many,” explains a medical source who prefers anonymity.

The first ones affected by Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) in Nicaragua were men: agricultural workers, with little access to drinking water. A profile already described in several of the scientific studies carried out that seek to define why, in this region, CKD is not only a consequence of diseases such as diabetes or hypertension (which is the traditional behavior of the disease), but also affects younger and, apparently, healthier people. But above all, why, if CKD is not a communicable disease, it has a specific niche in farming communities.

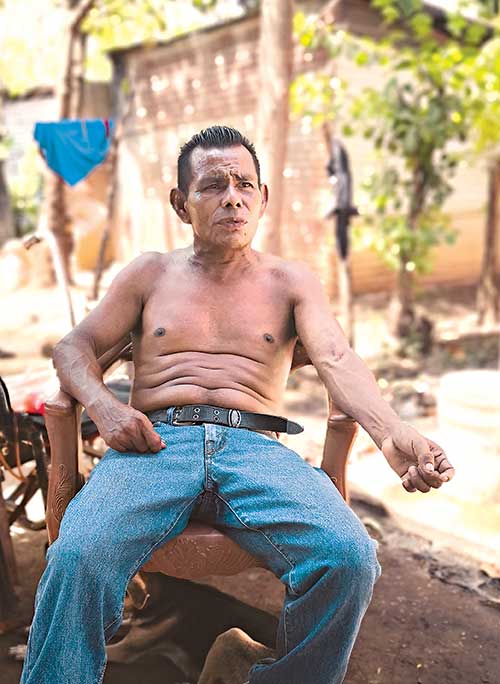

Juan de Dios Guzmán, this morning of February 2020, does not have enough fingers or memory to make a list of how many people from La Candelaria he has seen die from this disease. He prefers to summarize: “Here, we all have creatinine”, this is how Chronic Kidney Disease is known. He is with other neighbors in the patio of his house, a surface of the land and some stones where, with plastics and crooked sticks, he has made a kind of very precarious terrace. Juan is shirtless, the heat, the wind and the dust almost do not let speak. Hemodialysis marks are visible on his arms. They are bulging veins like balls.

Juan was a pailero -a person who cuts the sugar cane with the machete from the field-. Juan has been ill since 2002. Juan says he got sick from working at the sugar mill and living in this area. Juan has children. Juan’s children are paileros. Two of Juan’s children have Chronic Kidney Disease. “We don’t have anywhere else to go. If it isn’t there, there’s no work,” he says as he shrugs. This cycle is the same in most of the houses of La Candelaria. It’s not that the women in the house aren’t sick; they just don’t know, because they’ve never been tested. They don’t have health insurance.

“It’s a tragedy,” is how one of the doctors quoted by Boston University researchers in an independent report published in 2011 describes it. Another of the doctors estimates that the number of cases increases by 10-15% each year; and, pharmacist suggests that the cases increase exponentially: “About five years ago they began to fall like flies, almost every day a dead person appears or extremely sick with this disease.” This document collects the impressions of doctors and pharmacists who are in the front line of battle in diagnosis and treatment.

In 2019, a group of 17 scientists from different countries published another study in which they analyzed, for a year, the cases of 34 patients from El Salvador, Sri Lanka, India, and France. Professionals found in common “lysosomal lesions of proximal tubule cells associated with various degrees of epithelial atrophy and detachment of cell fragments present in 81.3% of kidney biopsy samples from patients.”

Carlos Orantes, Salvadoran nephrologist and one of the 17 researchers in this study says: “The person who suffers from this particular type of CKD has three characteristics as an element of development: poverty, environmental pollution, and unhealthy working conditions.” This document relates the exposure to agrochemicals with a propensity for kidney deterioration. “Geographical or residential provenance is very important in this; where you live, what you do, where you grew up, how you developed are the social determinants of this disease”, he adds from the headquarters of the Ministry of Health in San Salvador, capital of El Salvador.

The study published in scientific journals delves further into the profile of the patients: “They are young men, mainly agricultural workers, with common socioeconomic and occupational determinants that include a warm tropical climate, poverty, and exposure to potentially toxic substances, mainly agrochemicals to through ingestion of contaminated food, through drinking water from shallow contaminated wells, inhalation, and direct skin contact. It has been found among less exposed people, including non-farm workers, women, and children living in the same environment. ”

Chronic kidney disease of non-traditional causes is sown in farming communities, and regardless of whether the causes are not yet determined, the geographic component is undeniable.

Juan has been ill since 2002. Juan says he got sick from working at the sugar mill and living in this area. Juan has children. Juan’s children are paileros. Two of Juan’s children have Chronic Kidney Disease. “We don’t have anywhere else to go. If it isn’t there, there’s no work,” he says as he shrugs. This cycle is the same in most of the houses of La Candelaria.

***

La Candelaria is a cloud of light brown powder. In the middle, where the precarious houses stand, it’s impossible for them to be clean. The fine earth sneaks all over the place. And the intense heat forces you to go out, to take your shirt off, and to create shadows with plastics to be able to stay.

That’s how Juan de Dios is when he receives a visit from Jorge Romero. CKD, like dust, sneaks in the middle of every conversation.

—”They were taken out by commitment, to avoid problems, but they knew that all these people came stuck with creatinine,” says Romero, who is 65 years old, worked 14 harvests in the sugar mill, also lives here nearby and also has kidney damage. But he doesn’t need replacement therapy yet, the one in which a machine does the job that the kidneys lose.

—“Nobody has ever given us an answer to this creatinine thing. We have been waiting 20 years”-, points out Juan de Dios.

La Candelaria is the starting point for buses full of people who leave for the hospital of León every day. People take turns, because everyone must, at least twice a week, undergo the only treatment that worked among the people of Nicaragua: Hemodialysis. The other alternative, peritoneal dialysis was not massive, since it is domiciliary and requires basic housing and hygiene conditions that are not met in this settlement.

In La Candelaria there is electricity, but there are no sewers. As the former mayor Sevilla described it, the latrines are glued together. And so, too, are the people who live with CKD.

Juan de Dios is one of those patients who fill the buses, which are a service provided by the Chichigalpa city hall. There are so many that Juan belongs to the third group and, even later, there is one more. Every day, four buses with between 60 and 80 people leave La Candelaria for León, the white and tourist city, but they don’t do sightseen, they go straight to the hospital. It’s not just them. Here, in Chichigalpa, some people receive the treatment in Chinandega or Managua. They are various armies of people with withered kidneys. “And those are the sick, but alive. Of the old paileros there is almost no one left,” says Jorge, looking at the ground. Juan de Dios nods.

***

Nicaragua has always been agricultural. When it wasn’t sugar cane, it was cotton. These coastal lands have always been sown, always harvested, always occupied. The sugar industry already celebrated its 100th anniversary. People work here and to live here, they have been fighting space for crops.

“Our houses, our regions, our cities such as Chichigalpa, El Viejo, Pozoltega, Quezalhuate, and León itself, all are in the middle of the sugar cane fields. The natural environment of these populations is sugar cane,” explains the former mayor Sevilla.

In places like these, especially in Chichigalpa, separating residential from industrial areas is practically impossible. “The houses are in the middle of the sugar cane,” says Sevilla. He doesn’t exaggerate.

La Candelaria is the settlement from which the sickest comes out to receive treatment. There’s another town where the dead came from. It received media attention for it. It is called La Isla, but in the newspapers of several parts of the world, for about five years, it has been known as La Isla de las Viudas (The Island of the Widows). This is very common in the countries of this region, attention comes with death, not with sustained social injustices, such as safe access to housing.

Pedro Amador is wearing a dirty bandage covering his catheter. You can see it through his shirt when he extends his arms, as he is doing now trying to list his neighbors from La Isla who have died: “I don’t think I can finish that list today. Just here, on the other side, three went almost at the same time.” With other of his relatives present in this house, he puts together a list in less than two minutes: “Tino Calderón, Pedro Calderón, Felipe Calderón, they were brothers; Julio Altamirano, the other Julio, Salomón, Chepe Luis, Tomás Calderón, Aurelio, Virgil … “. Those only in recent years.

The Island is a community added to a sugar cane field. Pedro’s house is in front of a huge area of newly planted sugar cane. They are barely divided by a dirt path. The cane has its routines. It is sown, it is fertilized, and agrochemical is applied to it that is used to mature it. There are no walls here or any type of border. The fertilizer reaches the mango and avocado trees of Pedro’s house and, when that happens, the fruit rots. Then comes the burning, necessary to overcome the resistant texture of the reed, and then to be able to cut it. At this stage, Pedro, his family, the neighborhood, the municipality, the entire coast, breathe smoke.

Pedro Amador stopped working at the San Antonio sugar mill in 2001 when kidney damage was diagnosed in the same company. Since May 23, 2019, his chart became complicated and he became part of the dozens of men who, on La Isla, live with a catheter in their neck that serves to connect them to a machine that fulfills the function that their kidneys can no longer do.

Today, when he saw two women arrive, Pedro was happy. He thought we were representatives of the association to which he applied for a loan to buy the metallic sheets and fix his house. But no, we are only two journalists to whom he tells what it’s like to live and die among crops.

Pedro wants to show us the part of the roof of his house that is damaged. He makes numbers, he needs 22 metallic sheets to replace everything and to have one sheet left to leave an overhang. The sheets that for the moment are supported on four walls and protect the sleep of him, his wife, son, daughter, and grandson are corroded, broken. They don’t work. But, if he could remove them, Pedro would not throw them away. He plans to use them to cover the kitchen, which is outside. Because, inside, there is hardly any room for beds, a refrigerator, a table, a screen and a couple of furniture to put their clothes.

Pedro also needs some cement bricks. He does numbers again, adds, multiplies and, in the end, divides the sum he would borrow among all the months in which he could pay it. It doesn’t fit. When he talks about remodeling his house, his face covers him with illusion and frustration. “I am not telling you how much each sheet is worth, because I haven’t asked. I am afraid to, I have no courage to go,” he says today when he is wearing a white shirt with a red heart.

Although he wants to believe that he can borrow the 20,000 córdobas that he needs so that in the next rain nothing gets flooded, or so that the fertilizer from the sugar cane doesn´t impregnate all, he admits that he lives on a pension of 4,600 córdobas. He estimates he could pay a fee of 1,600 a month, and that would mean tightening his belt. People with kidney disease live longer because of the treatment. But not all other basic needs, such as the roof, are met.

Pedro wants to show us the part of the roof of his house that is damaged. He makes numbers, he needs 22 metallic sheets to replace everything and to have one sheet left to leave an overhang. The sheets that for the moment are supported on four walls and protect the sleep of him, his wife, son, daughter, and grandson are corroded, broken. They don’t work.

***

At La Isla, while Pedro has been talking, his wife is preparing a pot of soup. She is going to sell it. She has already cut the vegetables and has brought the meat to a boil. But what she has done most is draw water from the well. This is the form of supply that is here in most houses. This is a barely covered well and it is not tested to find harmful chemicals in humans. There was once an attempt to introduce piped drinking water service, but the institution leading the project was not even able to offer a service without long interruptions. People, like Pedro, preferred to continue with their well.

In La Candelaria, when Juan de Dios and Jorge talk, Juan’s wife does the laundry. Here there is a water service by pipeline. But they are not systematically checked either. And, if they are, the results of those controls are not made public. People do not know what kind of water they use to wash, cook, or drink.

The face of this disease is farmer men. But it is a face made based on incomplete data. A nephrologist who has been working closely with them for decades explains: “More male patients come because there are more men among insured. This statistic gives a fictional value, not a real one.”

With the outbreak of the Chronic Kidney Disease crisis in the early 2000s, changes in social security were also promoted. “At that time people died in their houses; it was horrible to see them with dry mouths, among high fevers, they said that they burned and that they had sand in their throats. They died in front of their loved ones,” recalls the former mayor Sevilla.

Then, the law required 750 weeks of work to be entitled to a reduced old-age pension. The law was amended in 2013 and then in 2015. Now it requires 250 weeks to be able to have a pension of 1,910 córdobas for people who do not reach the age of 60 that requires retirement. With this, health insurance coverage was extended and more workers were able to extend their lives thanks to the treatments. But the new cases didn’t stop.

The San Antonio sugar mill maintains strict security measures, according to those who have worked there. Among them, are pre-diagnoses, the prohibition of working in the company if you have kidney damage, scheduled breaks, and the indication to only drink water that is inside the facilities, employees cannot bring any liquid from outside. The representatives of the San Antonio sugar mill were asked for an interview, but we were not able to get a response and schedule it.

Between Pedro and Juan there is a common characteristic. They speak in the short term. Every time they figure out the future of wife and children, they do so from their absence. Juan only wants his already sick children to receive better health care than him. And Pedro wants to hurry to inherit a house with the roof in better conditions, at least without holes. It is what it is.

Glenda Girón, Bertha Fellow 2019-2020