Sonia’s little wooden room for dialysis

Chronic Kidney Disease has a mortality rate of 54% in Guatemala. Among the departments with more reported cases is Escuintla; here, 61% of the sugarcane cultivation area is located. On this coast of the Pacific Ocean, many communities are neighbors of large areas of crops. Farmers and their families live among sheets, plastics, environmental contamination, and high temperatures, without access to quality water and with progressive disease. One of them is Sonia, a kidney patient who must have her dialysis done in a makeshift room that is no more than a square meter.

The room has four wooden panels that do not reach the ceiling. Inside, there’s a green plastic chair, on a table a pink canister with water, and on the floor a red plastic bucket. For the hydration solution, there is no pedestal. A nail in the wall supplies that function. On the door, in green color letters with crooked and childish strokes, someone wrote: treatment room. An arrow, just as bent as the letters, marks the entrance.

This square meter is the place where 50-year-old Sonia Ruth Alpirez locks herself up for detoxification on peritoneal dialysis. Her kidneys no longer work. She cannot pee. Through a catheter -that can be seen above her navel-, she connects two hoses, one to enter the serum that hangs from the nail and the other to take it out and pour it into the bowl on the ground. She repeats this procedure three to four times a day.

Sonia lives in a village in Tiquisate, Escuintla; one of the departments of Guatemala that, for over ten years, has reported most cases of Chronic Kidney Disease.

The advance of this disease in Escuintla has been notable. In 2008, there were 114 cases, and the death rate was 17%. While by 2017, there were already 233 cases detected, and the death rate had already escalated to 29%. These are data from Guatemala’s Department of Epidemiology, Ministry of Public Health and Social Assistance.

Escuintla is a department located on the coast of Guatemala towards the Pacific Ocean. It is part of a cord of populations affected by a type of Chronic Kidney Disease with no other previous illnesses, such as diabetes and hypertension. For this reason, experts have agreed to call it Chronic Kidney Disease of non-traditional causes. Escuintla also appears in agricultural productivity reports. 61% of the sugarcane cultivation area is in this department.

This type of CKD has taken place inside the farming communities. It’s not just Escuintla, nor is it limited to Guatemala. In Mexico, El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Costa Rica, and Panama, a high and unusual number of cases reported for almost two decades. Those affected are people like Sonia -who has worked in agriculture or lives on plantations- and who has some degree of loss of kidney function.

The CKD in these communities is not an immediate death sentence. It can be detected in the early stages. By doing so, patients have the opportunity to get treatment and slow the progress of the damage. Most cases, however, are detected in more advanced stages, when the kidneys are no longer able to do their function, and people suffer a collapse. After that, they are tied to a substitute therapy, such as Sonia’s peritoneal dialysis. It’s not a cure; it is, barely, what keeps them alive.

Sonia tells the beginning of her story in a few words: “I started to swell, my breathing was difficult. They took me to the hospital and did tests. That’s when the doctor told me that I was sick with kidney failure. They treated me and put the catheter in once.” Before this, she had multiple episodes of UTIs but never found an opportunity to undergo a study more focused on detecting kidney damage.

Since August 4, 2012, Sonia must isolate herself in that cubicle that her husband built to do her detoxification process. At the same time, she follows a strict diet, cannot carry out physical activities, and, most importantly, she must limit her water intake, a significant challenge considering that, in Tiquisate, the temperature can exceed 38 Celsius. Sonia has been in this dynamic for eight years.

Sonia lives in the village Los Barrilitos II. And, here, she has more neighbors who have been diagnosed with CKD and also know of acquaintances who have died from the same disease. Every year, around 5,000 new cases appear in Guatemala. The departments with more CKD cases are Guatemala (capital), Santa Rosa, Petén, and, of course, Escuintla, to which Tiquisate belongs.

CKD from non-traditional causes has been the subject of several studies. However, it has not been possible to identify a specific reason for it. Some factors classified as risks are agricultural practices that involve intense work, heat stress, exposure to agrochemicals, indiscriminate consumption of anti-inflammatory drugs, and lack of access to drinking water.

Dr. Vicente Sánchez Polo, head of Nephrology and kidney transplant service at the Guatemalan Social Security Institute, adds more risk factors to what he describes as “the perfect storm” for CKD patients: the difficulty of finding health services, low to non-schooling, poor nutrition, and low birth weight. “Everyone just by living in that place, have increased kidney vulnerability because that’s where all the risk factors come together,” explains Sánchez Polo. He is also a member of the board of directors of the Center for the Study of Central American Nephropathy in Central America and Mexico (CENCAM).

El Barrilito II is like this. It is green, agricultural, and hot. It is a series of houses of sheet and plastic poorly placed on twisted sidewalks that become rivers of mud when it rains a lot. It is in this village where Sonia already lives only to connect to hoses four times a day in a wooden room. “Everything costs more with this disease. But the hardest thing to endure is bone pain, back pain, as well as having my lungs full of water, that’s how it feels,” Sonia tells from outside her house.

Among families in this area, it is not uncommon for CKD to be a diagnosis or a cause of death. What is rare is prevention. In Prevalence and Mortality of Chronic Kidney Disease in Guatemala (2008-2018), (published March of 2020), Dr. Berta Sam-Colop explains: “Patients with early stages of CKD are generally not diagnosed or treated promptly and frequently have multiple risk factors that increase the risk for loss of kidney function, the development of complications and early cardiovascular death.”

Sonia doesn’t live alone. She has a husband and eleven children. For them, and the rest of the residents who live in this “perfect storm,” the risk is high, and the prevention insufficient.

***

SONIA’S HOUSE HAS A TIN ROOF, painted walls, and a concrete floor. But living like this is not the norm in this municipality of Tiquisate. Most inhabitants have much less. In agricultural communities like this, there are houses built with boards and plastic and with a dirt floor where chickens dig, like the one where Francisco Santay, 58, another patient with CKD lives. Like Sonia, he lives in Tiquisate.

The land where Francisco has his house cost him 30,000 quetzals, equivalent to $3,900. He and his wife have five children. It took him and his family 11 years to finish paying this amount of money.

Strengthening the structure of the house was the most ambitious project they had when Francisco fell ill. Then, the sewage placement put in a hold. Now they don’t have any. And, since the conditions of his home are so weak and below what is considered worthy, Francisco is not a candidate for home dialysis. He must travel to the head hospital in Escuintla, two to three times a week, to undergo a machine-assisted detox called hemodialysis. These weekly trips came to complicate the family economy further. The family lost its ability to pay services, and now they don’t have electricity. Francisco, wife, and children have a debt of more than 1,800 quetzals ($235), here that kind of money is an impossible amount to collect.

In Guatemala, the qualitative housing deficit corresponds to 61%. This fact translates that of every ten houses, six have some or several issues, in poor condition. According to the study “Diagnosis of housing in Central America,” published four years ago, among the primary deficiencies are 29% of the houses have a dirt floor, and 22% have walls with defective materials, such as Francisco’s. “The lack of drinking water affects 9%, while the lack of easily accessible sanitary service in the home represents a very high 44% of the homes, as they lack this service in its entirety or only have a latrine,” the document describes.

These deficiencies become a greater danger in the case of families in which there are people with chronic and progressive diseases, such as CKD. Families like those of Sonia and Francisco. “This is the real problem of having health systems that are so deplorable and so weak, you do what you can,” says nephrologist Sánchez Polo, from the IGSS. And he adds: “We know that dialysis does not cure anything, it only serves to expel toxins, and the poor people have to do three to four replacements a day, what will happen to a poor farmer who does this process in a house with a dirty floor and with flies? He is going to have an infection.”

***

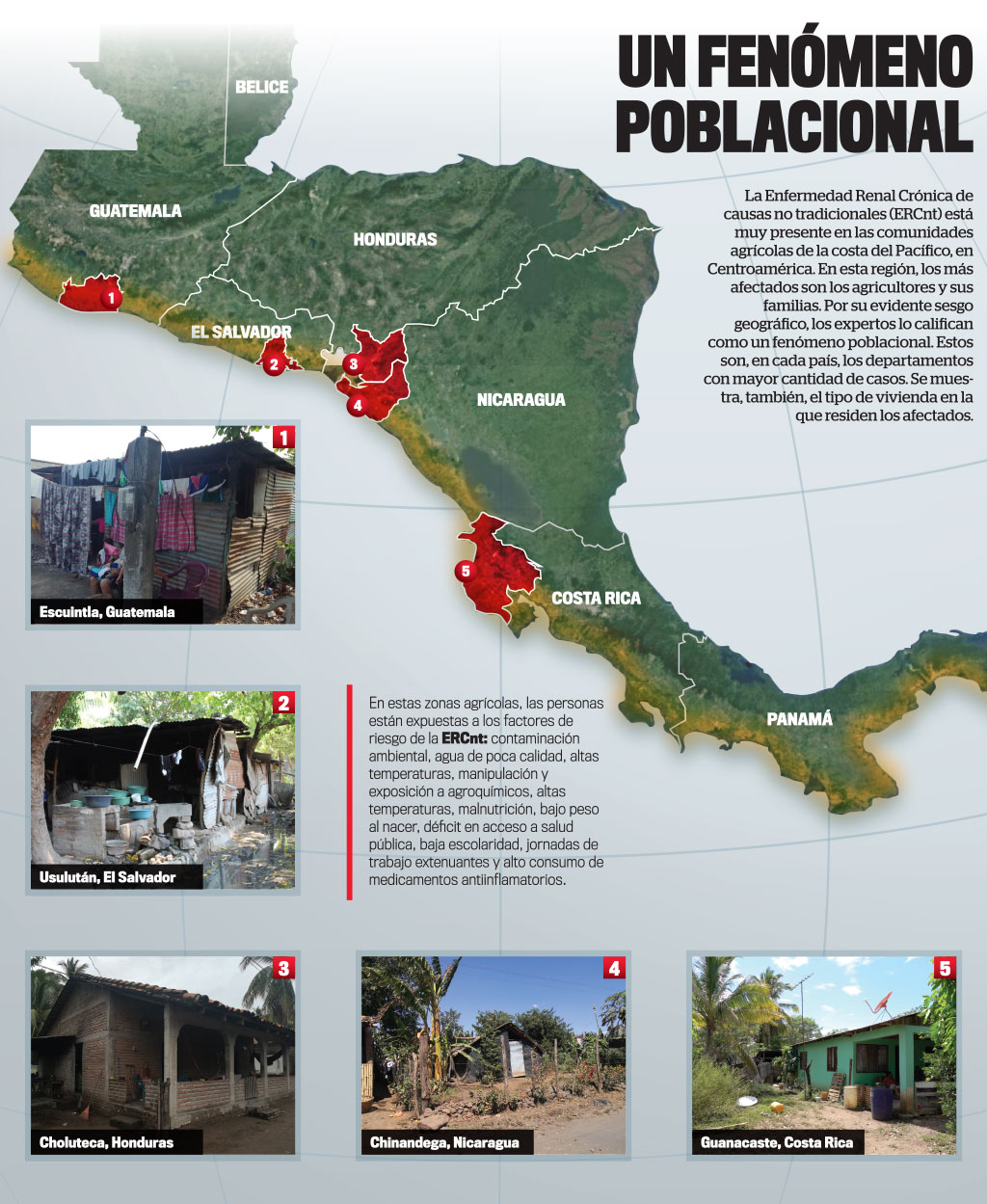

NON-TRADITIONAL CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE IN TIQUISATE, in Escuintla, Guatemala, is the same that has farmers and their families captive in Jiquilisco, Usulután, in El Salvador. And it is the same that causes anguish in Bagaces, Guanacaste, in Costa Rica. It also affects hundreds of people in Chichigalpa, Chinandega, Nicaragua. And this disease is the same in Marcovia, Choluteca, Honduras. As Dr. Sánchez Polo says, it is not just a medical problem; it is also a population problem.

“Un chico de estas zonas ya nace pobre, con dificultad de acceso a la salud, con bajo peso; cuando empieza a trabajar a temprana edad, sus reservas renales ya van disminuidas”, expone el doctor Sánchez Polo, y suma que la normalidad en estas comunidad incluye el consumo de agua de mala calidad, uso o exposición a agroquímicos, abuso de medicamentos antiinflamatorios, bebidas azucaradas, exceso de calor y esfuerzo físico extremo a la hora del trabajo. “Esto hace que esta sea una enfermedad más de carácter epidemiológico, poblacional y no solo relaciona a una causa, son múltiples causas”, agrega.

“A boy from these areas is born poor, with difficult access to health and low weight. When he starts working at an early age, his kidney reserves are already diminished,” explains Dr. Sánchez Polo. He adds to this situation the consumption of poor quality water, use or exposure to agrochemicals, abuse of anti-inflammatory drugs, sugary drinks, excess heat, and extreme physical effort at work. “This makes this a disease that is more epidemiological and not only related to one cause, but there are also multiple causes,” he adds.

In Latin America, countries with the highest mortality rates from CKD are Nicaragua and El Salvador. Just in El Salvador, deaths reach 2,500 annually. The populations most affected in each of these countries are on the Pacific coast. A document endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO) indicates: “This geographical area contains the largest portion of arable area, and agriculture, especially sugarcane has intensified in recent decades, which resulted in an increase in the cultivated area, a higher yield per hectare and greater productivity of the harvests”; this is how the document “Epidemic of Chronic Kidney Disease in farming communities in Central America,” published in 2017, describes the situation.

Escuintla, to which Tiquisate belongs, has 165 thousand hectares dedicated only to the cultivation of sugar cane. “Most of the national mills and cane production locates in the department of Escuintla, due to its strategic geographical location towards the main port of the country (Puerto Quetzal),” says a report from the Department of Macroprudential Analysis and Standards Supervision of the Sugar Sector.

Sonia hasn’t always lived here, in Barrilitos II. Before, she lived in another community in Tiquisate called San Juan de la Noria.

When viewed from a satellite map, San Juan de la Noria looks like a sharp point with very straight edges. What makes it that way are the crops. Hundreds and hundreds of green hectares surround it. The main economic activity is agriculture, and the predominant plantations are sugar cane, bananas, and African palm. These harvests represent 84% of the municipality’s production.

It was this agricultural character of the area that made Dr. Sánchez Polo and his team head towards Escuintla, where Tiquisate is, to conduct a study on the prevalence of Chronic Kidney Disease. In a sample that included 700 people of all ages, the researchers screened them. “We focus on a community that is located 200 meters above sea level, it is in a risk area, because several sugar mills surround it,” explains Sánchez Polo.

The results of that study are worrying. “We found that half of the children already have kidney damage,” says the researcher and nephrologist. These children are in school; they aren’t workers and, if they do some work, it’s not the whole day. Sánchez Polo explains that, although there are attempts to link CKD only to agricultural workers and this reduce it to an occupational risk, this is not a reality. Research like this, which includes populations beyond the mills, reinforces the idea of multiple causes. “We found that 30% of women who were housewives, already had kidney damage,” he adds.

Sonia, in fact, only worked in agriculture for a short time when she was a child and helped her father. Between 2008 and 2018, 35,877 people with CKD were registered in Guatemala, according to data from the service network of the Ministry of Public Health and the National Unit for Care of the Chronic Kidney Disease (UNAERC). In that same period, 19,491 deaths related to this disease were documented. The mortality rate of CKD in Guatemala is 54%.

The risk for the researcher and nephrologist Sánchez Polo is not just the job: “The fact that you live there already makes you a person at risk of kidney damage. Early detection and protection are required. But, in the same context of poverty, these people are not checked not cared for.”

For Sonia and her family, El Barrilito II’s house is, without a doubt, an improvement. “A blessing,” she says, which came to them through the evangelical church they attend. When asked if she would move from here, the answer is no. And, in this regard, she has only one request that she makes almost as a whisper: “Here, I would only improve my little wooden room so that I can get myself my treatment in a better way.”

Glenda Girón es becaria 2019-2020 de Bertha Foundation.